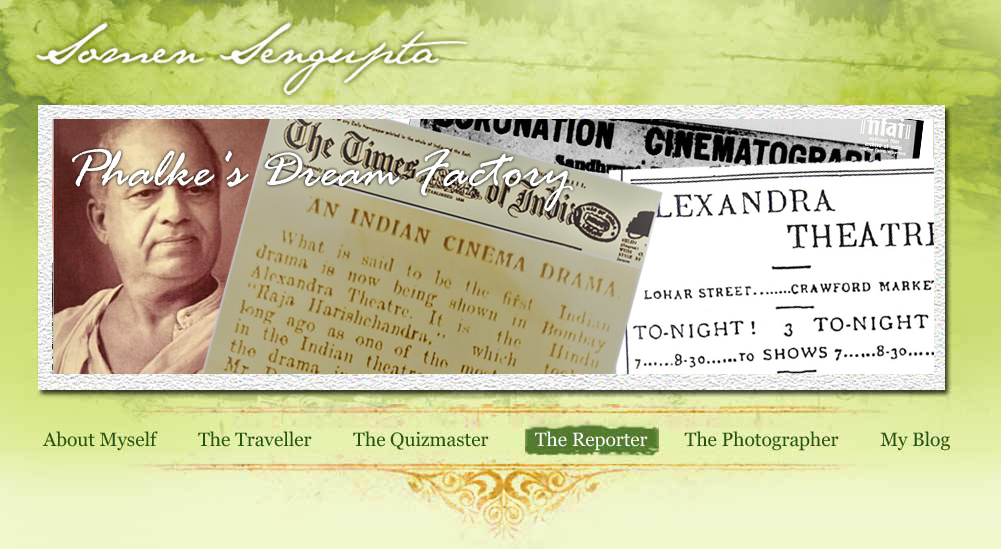

The Man Who Believed In Indian Cinema

The Statesman - 29th April 2022.

Released on 3 May 1913, Dhundiraj Govind Phalke’s Raja Harishchandra was the first complete feature film by an all-Indian crew.

A3,700 feet or four-reels-long silent movie of 40 minutes was released at Bombay’s Coronation Cinematograph on 3 May 1913, a year before World War I broke out and hardly a few months before Rabindranath Tagore won the Nobel Prize. The country’s tryst with the magic of motion pictures got an edge with the release of Raja Harishchandra, an indigenously made feature film, scripted and directed by Dhundiraj Govind Phalke.

A3,700 feet or four-reels-long silent movie of 40 minutes was released at Bombay’s Coronation Cinematograph on 3 May 1913, a year before World War I broke out and hardly a few months before Rabindranath Tagore won the Nobel Prize. The country’s tryst with the magic of motion pictures got an edge with the release of Raja Harishchandra, an indigenously made feature film, scripted and directed by Dhundiraj Govind Phalke.

He was in his early 40s when, for the sake of making the film, he left his government job. His infallible determination awarded him a place in history as the “father of Indian cinema”, though the title is strongly challenged by many. Cinema entered the Indian cultural space with the Lumiere Brothers’ exhibition on 7 July 1896 in Bombay. A bunch of extraordinarily talented people from Calcutta and Bombay started making motion pictures on all kinds of topics from politics to sports, and also stage adaptations, advertisements and news reels. It will be historically untrue if someone says that before Phalke Indians were not introduced to filmmaking. In fact, in 1901 in Calcutta, Hiralal Senpicturised a part of Flower of Persia from a theatre production, just like Ramchandra Gopal Torne did from a play named Pundalik, which was released in Bombay on 18 May 1912. But the latter’s cameraman was a British person named Johnson from Bourne and Shepherd.

On the other hand, Phalke’s Raja Harishchandra is a milestone movie because it was the first complete feature film, telling a dramatised version of a story on celluloid, by an all-Indian crew. It gave birth to an industry in India, which is now considered the biggest in the world. Phalke was born near Nashik on 30 April 1870 and educated at the J J School of Art, Bombay, and Baroda’s Kala Bhavan. A brilliant student of commercial art, he started working as a photographer and scene painter, and finally got a job at the Archaeological Survey of India as a draftsman. He, however, soon left the job to read more on making cinema and started collecting books on the subject. It took such a toll on Phalke’s health that he turned blind for some time and suffered financial constraints.

Once his eyesight was cured, he watched a movie named Life of Christ at Bombay’s America India Cinema. Then onwards, he started believing that cinema can be made in India by Indians, something unimaginable at the time.

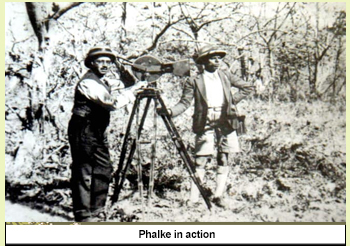

Phalke knew that this audacious venture needed sound technical knowledge backed by practical experience, and that led him to England, even though he was not well off. He somehow convinced his friend Yashwant Nandkarni and by depositing the latter’s insurance policy, collected Rs 10,000 and sailed to London on 1 February 1912. He managed to meet Cabourn, the editor of Bioscope Weekly and impressed him. Phalke could spend eight days with him discussing and experiencing many important aspects of filmmaking, and soon got to meet Cecil Hepworth, a British film director, producer and screenwriter, who gladly trained him in his studio.

Hepworth also helped Phalke buy a Williamson camera, projector, printing apparatus, manuals and raw film from Kodak. He returned to Bombay on 1 April 1912, and started practising filmmaking at home, capturing the many moods of his family members. In a few months, he accumulated a fund by mortgaging wife Saraswati’s ornaments and prepared a script, which went on to become the first indigenous feature film in India. Though Phalke managed to arrange a technical staff, finding artists, especially women, was near impossible.

Hepworth also helped Phalke buy a Williamson camera, projector, printing apparatus, manuals and raw film from Kodak. He returned to Bombay on 1 April 1912, and started practising filmmaking at home, capturing the many moods of his family members. In a few months, he accumulated a fund by mortgaging wife Saraswati’s ornaments and prepared a script, which went on to become the first indigenous feature film in India. Though Phalke managed to arrange a technical staff, finding artists, especially women, was near impossible.

Acting in cinema was a social taboo and a totally unknown skill at the time. He even selected a few sex workers for the female role, but they ditched him at the last moment. Finally, he decided to consider male actors to play the female character, and a cook named Anna Salunke got the key part of Rani Taramati. His son Bhalchandra Phalke played Harishchandra’s son, while the title role was played by a Marathi stage actor named Dattatreya Dabke. Phalke started shooting in a studio near Dadar Main Road and proudly called it a “factory”, where the finest products are made in the form of cinema. Little was he aware that one day filmmaking would become a huge industry with massive capital and manpower. The film was shot fast, with many outdoor sequences. Phalke, however, could not take his team to Banaras, which was the background of the story. All Banaras sequences were shot in various locations in Maharashtra. The set design and dress materials of the actors had a deep influence from Raja Ravi Verma’s mythological paintings.

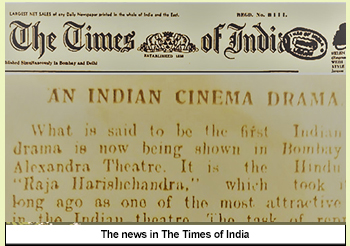

It took seven months and 21 days to complete the film. Finally, it premiered at the Olympia Theatre, Bombay, on 21 April 1913. It was supplemented by a dance show, comic act, foot juggling, etc. Raja Harishchandra took over Bombay from day one. It ran for 23 days, which was six times more than any standard film then. It was later shown at the Alexandra Theatre at Crawford Market, Bombay. Such was the enthusiasm around it that a popular daily reported, “... the result has been distinctly encouraging. There are minor defects, it is true, but bearing in mind the difficulties under which Mr Phalke worked, it is a great success.” It further stated that “the film will not appeal to the European community but with Indians it has become exceedingly popular. Already it has had an uncommonly long run to large and often crowded houses.”

The success of his first film pushed Phalke to make more movies on Hindu mythology over the next three years. He made Mohini Bhasmasur (1913) and Satyavan Savitri (1914). Lanka Dahan (1917) and Kaliya Mardan (1919) soon followed. Lanka Dahan was such a hit that it collected Rs 32,000 in 10 days from Bombay’s West End, and Pune’s Aryan Cinema got gate-crashed. In 1917, Phalke formed the Hindustan Film Company and the following year, he released another blockbuster, Shri Krishna Janma. In 1914, there was a demand for his films in England, where he went to show four of his works, but the outbreak of World War I jeopardised the plan. He suffered financially for the event. Phalke kept making films till 1934 and made nearly 125 feature films and a few documentaries. He, however, started fading from the limelight as Talkies overtook the Indian entertainment scene. Today, only 15 silent films of his are preserved at the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune. Raja Harishchandra’s first and fourth reels have survived but the rest are lost. Only Kaliya Mardan could be preserved in full.

Phalke may not be the pioneer of Indian cinema, but he is undoubtedly the trailblazer of Indian feature filmmaking. His dream gave Indian viewers a new mode of entertainment, and acting was recognised as a profession. That way, he is indeed the father of the Indian cinema industry.

Click here to view the original article |