| MCCLUSKIEGANJ: SAGA OF AN ABORTED DREAM |

|

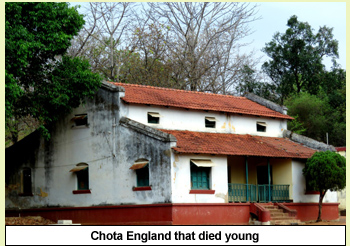

This ‘Chhota England’ of Jharkhand can be thought of as a time capsule in itself. But sadly, people have chosen to forget about it, writes Somen Sengupta

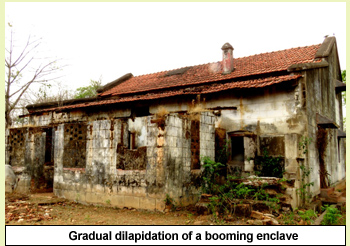

Near the station, a sign board proudly avows that it as the heritage village of Jharkhand. However, as soon as the leafy roads running zigzag in the jungle of tall sal trees and hills are taken, it gives a feel of a pathetic decay in tourism. Several dilapidated buildings and a vandalised cemetery will add more pathos to that tune. It is not Kerala where even an ordinary place is often presented as a tourist delight. It is Jharkhand, where an extraordinary place is reduced to rubble. Here, people are allowed to freely walk through a piece of history and are oblivious to its significance.

Near the station, a sign board proudly avows that it as the heritage village of Jharkhand. However, as soon as the leafy roads running zigzag in the jungle of tall sal trees and hills are taken, it gives a feel of a pathetic decay in tourism. Several dilapidated buildings and a vandalised cemetery will add more pathos to that tune. It is not Kerala where even an ordinary place is often presented as a tourist delight. It is Jharkhand, where an extraordinary place is reduced to rubble. Here, people are allowed to freely walk through a piece of history and are oblivious to its significance.

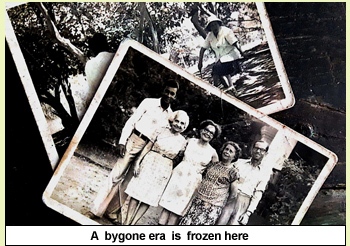

Without any doubt, the place gives a clarion call to a million hearts. It magnets those who created unforgettable childhood memories here between the 1940s and the 1960s. Also, some lovers of heritage are unofficially working to record a saga that history should not ignore. There was love for neither history nor heritage in the heart of Ernest Timothy McCluskie, an Anglo-Indian property broker from Calcutta. He managed to procure a huge chunk of land in the jungle from the king of Ratu in Chota Nagpur Plateau at a throwaway price in the early 1930s.

Just 60 km away from Ranchi, the then summer capital of Bihar (now in Jharkhand), this place was known as Lapra. Though connected by road and rail in 1933, it was practically a deep forest like landscape on the banks of Dugaduri river with no amenities to survive.

It was there that the first and only homeland for a homeless community was planned. It was there that McCluskie saw a dream. It was something that Sir Henry Gidney had hoped for a few years before McCluskie did, but had failed to materialize the same. The dream of a homeland for Anglo-Indians was not new. Gidney had once sent some Anglo-Indian families from Calcutta to Andaman Islands for the same purpose. But all of them either died there or just came back. It was there that the first and only homeland for a homeless community was planned. It was there that McCluskie saw a dream. It was something that Sir Henry Gidney had hoped for a few years before McCluskie did, but had failed to materialize the same. The dream of a homeland for Anglo-Indians was not new. Gidney had once sent some Anglo-Indian families from Calcutta to Andaman Islands for the same purpose. But all of them either died there or just came back.

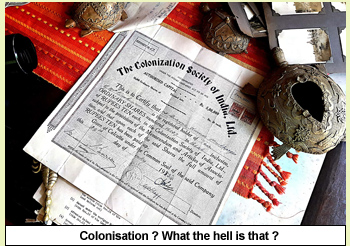

This time, McCluskie was more organized, better funded, and better planned. Immediately after getting the land, he and his friends formed an association named the Colonisation Society of India. The society published advertisements in the newspaper and sent communications to almost all Anglo-Indian families with European links across India, Sri Lanka and Burma offering land at a new place against purchase of their share. The land was offered as freehold with some condition in case of reselling, like it should be sold to Anglo-Indians or any other member of the society.

A dream was soon shaped for a community who were always in a pain of feeling isolated in a country like India for not having any clear acceptance and dignity in society. Being cross-parental biological beings, Anglo-Indians in many ways looked like Europeans with their pink skin, blue eyes and golden hair. But that was too small a merit for which a ‘pure European’ would never think of them as ‘his/her own’.

On the other hand, Indians found only disparity in the Anglican lifestyle as compared to theirs. Anglo-Indians spoke English, ate pork and beef, wore coats and skirts, and mostly significantly, they carried a Christian name. That created a gulf of sorts between them and mainstream Indians. A section of the Church-going community suffered from a superiority complex when it came to Indians and an inferiority complex when it came to pure Brits or Scots. It came attached with racial inheritance.

However, their fluency in English, physical fitness, love for games and almost unconditional loyalty to British Government for a partial ancestry helped them get employed in several important public sectors. From railways to customs or from the job of nurse to a private secretary of big corporate personnel, Anglo men and women had it relatively easier. In colonial era, every railway colony had an Anglo-Indian enclave where families used to celebrate their own lifestyle.

Some insight into history gives us some idea about how painful and perplexing the history of Anglo-Indians in India has been. They were never accepted as Indians by Indians. And in European community, they were always “no more than a the shaming evidence of sexual transgression by the lower mark,” as observed by Ian Jack.

At the initial stage, East India Company used to encourage its European employees to have Indian wives or mates for their physical needs. There was even an approval of compensation for fathering babies through Indian girls but the situation changed very fast. At the initial stage, East India Company used to encourage its European employees to have Indian wives or mates for their physical needs. There was even an approval of compensation for fathering babies through Indian girls but the situation changed very fast.

Their population was already increasing when in 1786, Lord Cornwallis came to India as Governor General. Fresh from defeat at the hand of George Washington in Yorktown of America, Cornwallis was a man who had no faith in honoring a mixed-race progeny. It was he who in 1791 banned orphaned children of Anglo-Indian soldiers to travel to England for education. In 1795, he issued a legislation to prevent the admission of any Anglo-Indian in East India Company’s army except as pipers, drummers, bandsmen or farriers. It was an injurious consequence that finally the community that looked European but was rooted in the soil of India, reduced to minor clerks, engine drivers, nurses, police inspectors, hockey players and office assistants.

McCluskieganj or the village of McCluskie, an enclave very near to a city like Calcutta, was an ideal sanctuary for many Anglo-Indians and soon 6500 acres out of 10,000 were sold to several families who almost overnight gave up the comfort of city life and shifted here for a better future. The jungle of Lapra started seeing gradual settlement of people with very different kind. Then came the Jemings, the Hourigans, the Merediths,the Barretts, the Perkins, and many more. With people, came a new culture and a new lifestyle that was not there in the British-ruled Bihar of the 1930s.

Anglo-Indian houses would have a fireplace, a red-tiled roof, a front veranda and open gardens on all sides. Double-roofed terracotta-tiled bungalows with provision of natural light through big outlets and running open verandas on front looking almost the same as any European country house gradually dotted the landscape of the jungle. Soon came along churches, clubs, bakeries, departmental stores, post offices, poultry, schools, assembly houses, and last but not the least, a Christian cemetery.

As the cemetery started filling up, it gave evidence of a large-scale settlement of people who had made this place their sweet home. The departmental store used to have a gala stock of goods that was even not available in Patna and Ranchi. The collection of imported whisky, cosmetics, dolls and gramophone records in shops was amazing.

Soon, all these houses started getting decorated with artefacts and vintage furniture with exceptional design. Followed by gramophone records, players, pianos, perfume bottles, fine wine, and guns, finally houses were converted into homes in that long coveted homeland. The best surprise came when overjoyed Anglo-Indians started arriving at the station. With them, came new music, new culinary and new language of Anglo-Indians. A mouth-watering bakery that was producing loaf, cake and cookies was started by Mr and Mrs Kearney. Another old lady named Mrs Dorothy Thipthorpe became famous for her homemade jam, jelly and squash. It was indeed a gala time. But, it did not last long. After her husband’s death, Mrs Kearney carried her business for long and finally made her cake famous in all of Bihar. Guns were useful for those newly-arrived dwellers as leopards and bears were regular visitors of the locality; they had no plan of co-existing with the human settlement. So, man-animal conflicts in the first few years were frequent. Soon, all these houses started getting decorated with artefacts and vintage furniture with exceptional design. Followed by gramophone records, players, pianos, perfume bottles, fine wine, and guns, finally houses were converted into homes in that long coveted homeland. The best surprise came when overjoyed Anglo-Indians started arriving at the station. With them, came new music, new culinary and new language of Anglo-Indians. A mouth-watering bakery that was producing loaf, cake and cookies was started by Mr and Mrs Kearney. Another old lady named Mrs Dorothy Thipthorpe became famous for her homemade jam, jelly and squash. It was indeed a gala time. But, it did not last long. After her husband’s death, Mrs Kearney carried her business for long and finally made her cake famous in all of Bihar. Guns were useful for those newly-arrived dwellers as leopards and bears were regular visitors of the locality; they had no plan of co-existing with the human settlement. So, man-animal conflicts in the first few years were frequent.

It was the time when for the first time, Anglo-Indians started to see India as their homeland. Still, the saga of confusion prevailed. The place soon became famous as “Chota England,” meaning “Little England”. The co-operative society was also formed with a very controversial name. The Colonisation Society of India was a name unacceptable to any patriotic Indian. The question was — how can an Anglo-Indian who claims to be a part of India, take pride in a piece of land in his/her own home being colonised?

This puzzle was never solved. It caused damage to any sense of affinity that was created between Anglo-Indians and other Indians — the former had started thinking of themselves as superior to the latter. This was also the time when India was quickly transforming into a new nation. After India’s independence, the nation practically forgot about Anglo-Indians.

Soon after his death, friends of McCluskie built a memorial fountain in his name. That is perhaps the first and the last memorial outside a cemetery that McCluskieganj has seen till date. But today, most commoners of the village don’t know where it is located. If one is lucky , they might meet a few old timers who had seen the heydays of the town. Now, standing inside a hostel, the fountain reflects the crumbling face of heritage. For those who care enough, the marble plaque erected on the fountain is an evidence of its past glory.

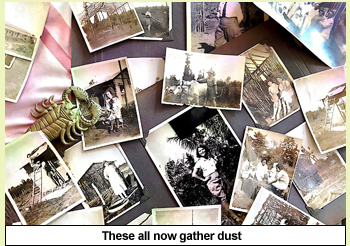

Old timers like Majid Ansari still take pride in relating the town’s stories from the “Angrezi zamana”. He who was once a part of the famous bakery of McCluskieganj ran by the legendary lady Mrs Kearney still has printing blocks and old photos of that institution. The bakery is long gone and even the building is razed. What’s left is just a few old papers and printing blocks of cake boxes that Majid still shows proudly to any visitor who wanders into his hut. Old timers like Majid Ansari still take pride in relating the town’s stories from the “Angrezi zamana”. He who was once a part of the famous bakery of McCluskieganj ran by the legendary lady Mrs Kearney still has printing blocks and old photos of that institution. The bakery is long gone and even the building is razed. What’s left is just a few old papers and printing blocks of cake boxes that Majid still shows proudly to any visitor who wanders into his hut.

Once churches were set up and clubs started functioning, socialising in the community reached its zenith. There was a time when every Sunday morning, the church was full of thousands of devotees. Church bells kept people far and near posted on the time. Easter and Christmas were gala events there. There would be merrymaking over mouthwatering Anglo-Indian cuisine. More magic was added to it with the divine aroma of baked cake, pudding and other typical westernized snacks that had the perfect fusion of Indian spices. Clubs and homes were decorated with festive lights and buzzed with music from grand pianos and saxophones. New Year’s Eve was marked by ballroom dancing and midnight kissing. But, “Chhota England” was a dream that had to die young.

Today, St John’s church stands in an unkempt garden that has a broken-wire boundary. The only glory left is perhaps a marble plaque placed on its wall that reads “ To the Glory of the God, June 24, 1940”. The other church is opened only on Sunday, mainly for local Christians. However, both the churches are well maintained till now.

On the right side of the railway crossing, a narrow road leads to the graveyard of McCluskieganj. This graveyard is another classic example of utter vandalism and loot. Almost all marble slabs and statues are looted and defaced. The few that have survived are cracked. Letters are mostly illegible. Still, even in that mess, gravestones give testimony to a buzzing enclave of Anglo-Indians in India. People who died between 1933 and 1970 have been laid to rest here. Emotional words carved on their gravestones by their loved ones tell varied stories of people who lived in those times. But some graves are bare and the cross installed over them is broken. A new cemetery has been opened close to the damaged and disregarded old one.

Thanks to the romantic aura and richness of legacy, this place had once became a favourite with rich people of Calcutta and Ranchi who were into country homes. This was in the early 19650s when one after another Anglo-Indian family was leaving the place. There was a time when people like filmmaker Aparna Sen and noted Bengali author Budhadeb Guha owned old colonial bungalows here. In 1962, a Bengali film named Shiuli Bari starring the legendary Uttam Kumar was shot here. Ever since, the place became a hotspot for tourists from Bengal. Today, many of the bungalows have been renovated under new ownership.

Dipak Rana, who comes from the royal family of Nepal and Tripura, came to this place in 1962 and decided to stay here. He got a property from a family whose son was a police officer in Calcutta. Dipak was born and brought up in big cities and got his education in Calcutta’s St Xavier’s College. He had no regret in resettling in the deep jungles of Sal. When he came there, there was no electricity, no roads and no luxury of anything that could be compared with life in a metro but still the magic of “Chota England” engrossed him. Today, he runs a home-stay hotel decorated with antique artifacts and vintage furniture. Dipak Rana, who comes from the royal family of Nepal and Tripura, came to this place in 1962 and decided to stay here. He got a property from a family whose son was a police officer in Calcutta. Dipak was born and brought up in big cities and got his education in Calcutta’s St Xavier’s College. He had no regret in resettling in the deep jungles of Sal. When he came there, there was no electricity, no roads and no luxury of anything that could be compared with life in a metro but still the magic of “Chota England” engrossed him. Today, he runs a home-stay hotel decorated with antique artifacts and vintage furniture.

The dream of Anglo-Indians dried up soon mainly because of an irrational plan of winning subsistence. City-born-and-bred Anglo-Indians were good at many things, but agriculture was not one of them. So, the plan of a life with farming and cattle grazing turned out to be the most impractical thing for those who were comfortable in running railway engines or playing the guitar at city hotels. Bihar turned harsh to them when they were faced by the challenge of job. In the absence of viable sources of income, most of the families found the kitchen fire not running. Soon after the independence of India, the new nation did not show any special love to them. As for Britain, it was economically devastated after the World War-II and had no sympathy to show. So, once again, Anglo-Indians were abandoned. Most of them shifted to countries like Australia and Canada where immigration was easy. Some even moved back to Calcutta and Bombay to start a new life. With their departure, the locked houses started collapsing. Today, out of 350 European bungalows, most are dilapidated. The roof is leaking and walls are cracked; tiles are missing and window panes are smashed. The verandas are dumped with broken bricks and woods and wild vegetation has engulfed the roof. Almost every bungalow is either deserted or very thinly occupied. Some of those have been locked for years. Bats and spiders have built kingdoms there.

In 1997, Alfred George D’Rozario founded the Don Bosco school here. That pumped new blood into the blocked heart of McCluskieganj.Today, thanks to this school, there are at least 20-odd hostels for students opened in many colonial bungalows. Some of those are managed by Anglo-Indians. Today, there are hardly 10 families of Anglo-Indians that stay in McCluskieganj. Their customs are now fully mingled with those of the local people.They refuse to talk to outsiders who come to see them as museum pieces. One can find them on an odd book cover or in a news feature.

Kitty Texeria, a 66-year-old woman, has become a poster girl for the crumbling legacy of Anglo-Indians of McCluskieganj. Like many others of her community, she no more sells oranges at station. She is married to a local man and has several children. The only ‘legacy’ that she has kept is in her name. She is still “Kitty Memsaab” to the locals. It’s a name she loves to hear.

This article was published in The Pioneer on 29th April 2018

Click here to view the original article

|