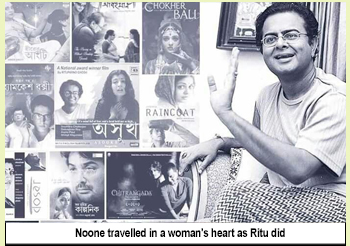

Rituparno Ghosh: The man who celebrated womanhood on screen

The Statesman dated 26th May 2023

From Meheboob Khan’s Mother India in 1957 to Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala in 1987, Indian cine-goers had seen the tangible emergence of women in a society which is known to suppress women’s individuality in the most brutal manner for ages.

From Meheboob Khan’s Mother India in 1957 to Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala in 1987, Indian cine-goers had seen the tangible emergence of women in a society which is known to suppress women’s individuality in the most brutal manner for ages.

However, Indian cinema had to wait for a few more decades to see womanhood on screen instead of only woman empowerment. The one who time and again established the idea of celebrating womanhood on the Indian silver screen was none other

than Rituparno Ghosh of Bengal, to whom destiny had given only 21 years to show his creative expression.Except for a few like Hirer Angti, his first film Ritu tried to tell the story of women in various forms and in multiple perspectives.

His introspection of a woman’s mind and body directly over-casted his scripts, story, dialogues, costumes and even in set design. It is pointless to discuss whether his own effeminate instinct which he was never ashamed to acknowledge openly was an aggregator in his thoughts but hardly there is a doubt that Ritu’s human quality and rich merit of wisdom moved him to make cinema where life of a woman comes at the central theme.Take a look at Shubho Mahurat,

released in 2003, a crime thriller. where we see a planned murder of an actress, and the mystery unfolds to expose an old enmity. Surprisingly, Ritu himself hated to categorise this film as a murder mystery.

According to him, it is a story of human relationship and human instincts when they are mentally devastated.

He made the film to show how two women, played by Sharmila Tagore as Padmini Chatterjee and Ranga Pishi played by Rakhu Gulzar, are trying to fulfil the void and isolation of their individual lives. While isolation of Padmini is forcing her to take a revenge on her dead son, the same isolation is helping Ranga Pishi to get engrossed in books and using her brain to solve a murder case just out of curious passion.

Ritu’s Ranga Pishi is a widow from a young age, but not vanquished, whereas Padmini, who is a former superstar of the silver screen, is badly defeated in a mental battle of life. However, at the end of the cinema, Ritu talks through Padmini, where she says “nothing comes back”. This small dialogue concludes the whole cinema in a second. The last 15 minutes or so, the film moves only through the dialogues between two elderly women who had seen two very different spectrums of lives. It was matchless in any Indian contemporary cinema. Ritu’s Ranga Pishi is a widow from a young age, but not vanquished, whereas Padmini, who is a former superstar of the silver screen, is badly defeated in a mental battle of life. However, at the end of the cinema, Ritu talks through Padmini, where she says “nothing comes back”. This small dialogue concludes the whole cinema in a second. The last 15 minutes or so, the film moves only through the dialogues between two elderly women who had seen two very different spectrums of lives. It was matchless in any Indian contemporary cinema.

Ritu’s first national award came from his 1994 movie, Unishe April, that dealt with the complex relationship of two women who are mother and daughter, played by Aparna Sen and Debasri Roy. This is not the only film where Ritu talked about a mother-daughter’s simple yet complex relationship.

In the 2002 movie Titli, we see almost similar sequences where mother and daughter cross paths for the same man in their lives and the love of a daughter for her mother turns pensive and complex only for that. In Unishe April, a daughter’s rock solid grievance and frustration against her career- centric mother take us almost to the middle of the cinema and the climax shows that the mother understands the emotional crisis of the daughter. From there we see an effort from both sides to build up a bridge at least through some open communication and exchange of pangs, which as the background of the story gives us the idea was long overdue.

In the last scene, we see that the daughter finally gathers courage to receive the STD call, while her mother stands next to her. Ritu was more than perfect in his delivery to establish that a relationship rebuilds when there is

communication and a woman can make it even if she is late. However, Ritu treats the same challenge in a very different way in Titli, where the story takes us to a point to believe that both mother and daughter have the same love interest in the character played by Mithun Chakraborty. In the last scene, we see that the daughter finally gathers courage to receive the STD call, while her mother stands next to her. Ritu was more than perfect in his delivery to establish that a relationship rebuilds when there is

communication and a woman can make it even if she is late. However, Ritu treats the same challenge in a very different way in Titli, where the story takes us to a point to believe that both mother and daughter have the same love interest in the character played by Mithun Chakraborty.

Ritu does not try to go overboard to show that the mother fully submits herself to her old flame. He makes her adequately sophisticated in her characterisation. He keeps her in the present state of life but shows her emotional tumult in her soft and humble gesture.

On the other hand, the teenaged daughter after overhearing the conversation between her dream superstar and her mother breaks into tears and in the rest of the movie keeps an emotional distance from both of them.

Ritu in Titli had a chance to recreate another Unishe April-sort-of-scene, but his profound understanding of the woman’s mind pushed him to think differently and the film ends with a complex relation underneath between two women. The

mother daughter pair of Titli was very different from Unishe April and the credit goes to the director who wrote both the story lines. Ritu in Titli had a chance to recreate another Unishe April-sort-of-scene, but his profound understanding of the woman’s mind pushed him to think differently and the film ends with a complex relation underneath between two women. The

mother daughter pair of Titli was very different from Unishe April and the credit goes to the director who wrote both the story lines.

The magnum opus of Ritu was Chokher Bali, released in 2003. The room is different to debate to know how far Ritu changed Rabindranath in his film but there can not be any debate to say how exceptionally Ritu celebrated women in this film.

The famous novel of Tagore was written in 1905-06 and its background starts in 1902, where we see a young Binodini, played by Aishwarya Rai, gets married and becomes a widow while in her blooming youth. The house where she comes to live with two old widows also belongs to her childhood friend Ashalata, played by Raima Sen. Ashalata is a child bride who is happily married to a man, who once refused Binodini, and here comes a woman out of Binodini, who has lustre, passion, greed, envy, thirst for love and every other instinct of a human being.

Ritu, frame by frame, with small dialogues, slowly builds Binodini, the woman who loves to live a normal life and does not want to suffer like in the life of a Hindu widow. Ritu shows to the audience love bites and nail wounds on

the body of Ashalata, who proudly displays it to Binodini to show her satisfied conjugal life. This flames up Binodini’s desire for physical needs and we see a sequence where she lies on a mat, slowly gliding her one hand over the

other to derive physical pleasure. As the story moves forward, Asha’s husband gets intimate with Binodini which gives the latter a winning charm over Asha,who enjoys every single materialistic pleasure of life only because of her living

husband. The story turns to an exceptional direction when Behari, a young lad, comes into their lives and Binodini seriously falls for her. The story turns to an exceptional direction when Behari, a young lad, comes into their lives and Binodini seriously falls for her.

Behari’s initial apathy makes Binodini dejected but later Behari agrees to marry her. There in Ritu’s film, comes a twist, when at the last moment, Binodini refuses to marry Behari – while, on one hand she leaves Mahim to get burnt in envy, on the other hand, she rejects Behari’s mercy in the form of marriage.The film comes to an end, showing a separation of Binodini from Ashalata and there go a few lines on the screen saying though the partition of Bengal was prevented in 1911, it could not be stopped 42 years later. Was it a calculated application to mingle partition of Bengal with separation of friendship of two women in Ritu’s film? In Tagore’s novel, this aspect was unimaginable as Tagore did not live to see Bengal’s partition in 1947. So, it was a pure superimposition of Ritu’s thoughts to illustrate the two Bengals as two women who were poles apart in their experience of lives, if not in their political thoughts. Here, Ritu consciously blends nation and woman in one capsule. Ritu touched almost every single shade of an Indian woman at various timelines.

If Antarmahal (2005) is a naked reality of women’s suppression in the late 19 th century Bengal, marital rape shown in Dahan (1997) is also the same wrong conduct done to women in modern times. In Dahan, when the character played by Indrani Haldar comes to her grandmother, played by Suchitra Mitra, we get to hear another shocking line. The grandmother tells her that she could not complete her graduation because her grandfather did not want that in fear of seeing his wife becoming an equal to him. The hidden male chauvinism over woman is palpable in Dahan and we see from the sequence of the molestation attempt at the metro station to the marital rape and even in the dialogue mentioned above. If Antarmahal (2005) is a naked reality of women’s suppression in the late 19 th century Bengal, marital rape shown in Dahan (1997) is also the same wrong conduct done to women in modern times. In Dahan, when the character played by Indrani Haldar comes to her grandmother, played by Suchitra Mitra, we get to hear another shocking line. The grandmother tells her that she could not complete her graduation because her grandfather did not want that in fear of seeing his wife becoming an equal to him. The hidden male chauvinism over woman is palpable in Dahan and we see from the sequence of the molestation attempt at the metro station to the marital rape and even in the dialogue mentioned above.

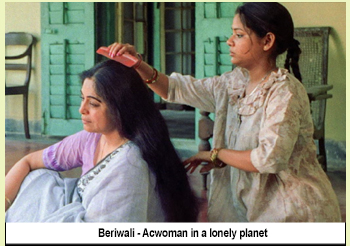

Ritu’s Bariwali is a storyof a lonely woman – a woman who owns a mansion where she lives with a few servants and haunting memories of her childhood.

Her silent pangs come clear when she takes out her wedding card which was printed but never used, as the marriage was cancelled due to the sudden death of the groom by a snakebite. She in her late fifties or so still had kept a copy of that card and in her dream, comes memories, where she sees a marriage mandap empty. Ritu in this film navigates in the fragile mind of a woman who apparently had accepted her misfortune but never gave up her hope to live.

The film shows a group of filmmakers coming to her mansion and she, by chance, gets to play a brief role in the film, thanks to the young director. As her heart slowly melts for him, the party suddenly leaves and she comes

to know through a letter that her scene is edited out of the film. The lone woman comes back to her lone world once again.

Has anyone before Ritu tried to show titbits of a woman’s life in daily life ? In a fragmented yet convincing way, Ritu dares to show Binodini’s menstrual blood on the floor in Chokher Bali and inhaling of the smell of fried fish by

a widow in the same film. This is more than an extraordinary imagination coming from a male director’s mind. Has anyone before Ritu tried to show titbits of a woman’s life in daily life ? In a fragmented yet convincing way, Ritu dares to show Binodini’s menstrual blood on the floor in Chokher Bali and inhaling of the smell of fried fish by

a widow in the same film. This is more than an extraordinary imagination coming from a male director’s mind.

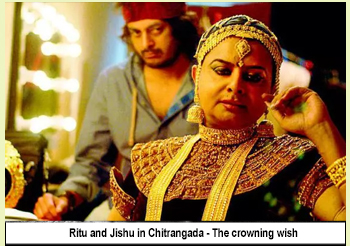

In the film Raincoat, Ghosh presents a woman as an unvanquished warrior of love. The role carved out for Aishwarya Rai resembles a human who pays a price for her old passion. Despite being poverty striken and trapped in a failed marriage, she reaches out to help her friend who is in a financial crisis. During the last stage of his life, Ritu made Chitrangada The Crowning Wish (2012).

This is a film, where Ritu the person became bigger than the film.

That might have dented the intellectual merit of the movie but here again,Ritu proved his extraordinary sensitivity to cultivate a woman’s mind. It was even a tougher job because the storyline is based on a man named Rudra Chatterjee who physically wants to become a woman to materialise his wish. The character Rudra was played by Ritu himself and that was a huge message to the society.

Ritu made it clear in this film that a person has the right to choose his/her/their gender as per his/her/their wish. His character in the movie says in a dialogue that “Chitrangada is a story of wish – her father wanted her to be a boy but she saw herself as a girl” . Ritu made it clear in this film that a person has the right to choose his/her/their gender as per his/her/their wish. His character in the movie says in a dialogue that “Chitrangada is a story of wish – her father wanted her to be a boy but she saw herself as a girl” .

Ritu, through Rudra’s form, shows the conflict of double existence of an effeminate man, who falls in love with a man named Partha, played by Jishu Sengupta, goes physical with him, dreams to build a family with him and even turns envious when Partha goes emotional with another female. At the same time, Rudra, as an effeminate, fears the surgery of recreation of the vagina, for which he gets admitted in a hospital.The bold movie shows us a sequence where Rudra enthusiastically displays his artificially developed breast to his lover Partha, but Partha, then in a relationship with a woman, finds it obnoxious. He says, “cover it”.

With this, Ritu makes his spectator believe that womanhood is beautiful only when it is natural and the master stroke comes at the last scene when on the operation table, Rudra gets to hear from his doctor that even Partha,

who is no more in his life also believes that he should go for a sex change because “just be what you wish to be – it is your wish “. By this single dialogue, Ritu makes womanhood victorious among all.

Rituparno Ghosh was proud of his effeminate existence and he was confident of his ability as a filmmaker, editor, writer and designer, and this audacity was candid in his every single movie.

Ritu’s creative world of cinema opened before us at a time when Satyajit Ray was no more, both Mrinal Sen and Tapan Sinha had passed their primes and Tarun Majumdar was making few forgettable movies. At that point of time, young, modern and feminist Ritu forced the urban middle class to go back to the theatre to watch Bengali movies and in every movie, he unashamedly celebrated womanhood in the most versatile and solid format.

The author is a freelance contributor

Click here to view the original article

|