The Rays' cinematic reunion: A glimpse into Sukumar Ray's world

The Statesman dated 29th September 2023

In the year 1961, a significant tribute was paid by the renowned filmmaker and author Satyajit Ray.He chose to resurrect Sandesh, the beloved children's magazine originally established by his grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury. This heartfelt endeavour was not only an homage to his grandfather's legacy but also a poignant acknowledgment of the immense contribution made by his father, Sukumar Ray. Under Sukumar Ray's remarkable editorial guidance,

"Sandesh" had achieved iconic status,

becoming a household name throughout Bengal.

In the eight years that Sukumar

got to take over the editorship of

Sandesh, he wrote and illustrated

innumerable pieces that are revolutionary in any sub-adult literature in

the world. So Sandesh, the magazine

again relaunched under the editorship

of Satyajit Ray and Subhash

Mukhopadhay in 1961, was actually a

giant step to rediscover the world of

Sukumar Ray, who died in 1923 just at

the age of 35.

In the year 1961, a significant tribute was paid by the renowned filmmaker and author Satyajit Ray.He chose to resurrect Sandesh, the beloved children's magazine originally established by his grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury. This heartfelt endeavour was not only an homage to his grandfather's legacy but also a poignant acknowledgment of the immense contribution made by his father, Sukumar Ray. Under Sukumar Ray's remarkable editorial guidance,

"Sandesh" had achieved iconic status,

becoming a household name throughout Bengal.

In the eight years that Sukumar

got to take over the editorship of

Sandesh, he wrote and illustrated

innumerable pieces that are revolutionary in any sub-adult literature in

the world. So Sandesh, the magazine

again relaunched under the editorship

of Satyajit Ray and Subhash

Mukhopadhay in 1961, was actually a

giant step to rediscover the world of

Sukumar Ray, who died in 1923 just at

the age of 35.

Ray again offered his literary tribute to his illustrated father in 1966

when he translated many poems from

Abol Tabol (The Ridiculous) and the

collection Nonsense Rhymes of Sukumar. Ray opened the door for nonBengali readers to read Sukumar. With

his extraordinary command of both

Bengali and English, Ray did almost

equal justice to the English translation.

His father's extra-ordinary power of

imagination and peerless selection of

words were converted into English

with no loss of magic in most of the

translation.

Ray got the best chance to offer

the richest tribute to his father in his

birth centenary year of 1987 when the

Government of West Bengal offered

him to make a documentary on Sukumar Ray.

Cinema, the most adorable form

of art to Satyajit Ray, was perhaps the

best way to pay homage to his father,

but this time luck was not on Satyajit

Ray's side. It was a time when he was

slowly recovering after a prolonged

period of suffering from heart disease.

He has been partly bedridden and

homebound since 1984. He was not

doing any films or even travelling

unless it was very essential.

Thus, when the offer landed on

his lap, he accepted it, knowing his

limitations as a director.

The biggest challenge of making a

documentary on Sukumar Ray was

that there was no film footage of the

man. For any biographical documentary film, footage of the man in the

subject adds huge visual delight. Ray,

while making a documentary on

Rabindrnath Tagore in 1961, was

blessed with several film clips and

newsreels of Tagore taken both in

India and abroad. This time, deprived

of such elements, he was forced to

depend on old photographs, illustrations, newspaper clips, old family letters, diaries, etc. With this, Ray had to

recreate the magic of his script-writing perfection for documentaries that

the world had seen in Rabindranath

Tagore, Sikkim, Bala and Inner Eye.

The first thing that made it difficult for Ray to make a documentary on

his father was his misfortune of not

knowing him personally as a son. Ray

lost his father in 1923, when he was

just two and a half years old. So many

times Ray has said clearly that he is not

introduced to his father as any son

does, but rather that he knows him

through his world of creativity.

This disadvantage of not knowing a father but only knowing an iconic

literary genius named Sukumar Ray

actually converted into an advantage

to the director because it prevented

him from going overly emotional at

any point in the entire film. Ray, unlike

recreating childhood scenes from the

Rabindranath Tagore documentary,

just used many black-and-white photographs of Sukumar and his family

members at the beginning of the film.

In the first 12 minutes or so, Ray navigates into the world of the Ray Chowdhury family with a lot of known and

unknown facts through the background commentary rendered by

Soumitra Chatterjee. The best part of

that part is telling the rich cricket legacy of his family, a fact not known to

many people before the era of Google.

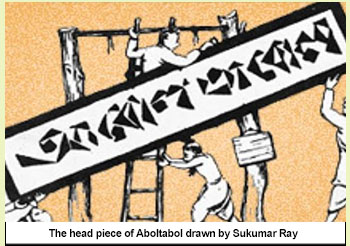

Sukumar's role and efforts to

make Sandesh a leading children's

magazine of that time are very visible

in the film. Ray salvaged and showed

many rare cover designs, headpieces,

and illustrations done by his father for

Sandesh. In a nutshell, he exploited the

unseen archive of the magazine to a

great extent, which no doubt enriched

the film. It is a visual delight to see the

colour paintings of Sukumar and his

modern printing output on the pages

of his edited magazine.

Ray spent a considerable amount

of time connecting Sukumar's close

relationship with Rabindranath

Tagore. He mentions Sukumar's association and Tagore's affection for this

talented servant of Bengali literature.

In the documentary, we get to see a

group photo taken in London in 1912

where a young Sukumar Ray, then

doing higher studies in printing and

photography in England, is seated next

to Tagore, who was travelling to England with his English translation of

Gitanjali. The film shows Sukumar's

article on Tagore's literary work, which

was published in London's famous

Quest magazine. It talks about the

movement launched by Sukumar and

his young friends of Bramha Samaj to

include Tagore in its committee, and a

small booklet with the title "Keno

Rabindratha ke Chai" (Why

Rabindranath is required), then published by the young gang, was also

shown.

As an editor, Sukumar Ray convinced Tagore to contribute to

Sandesh. A clip comes on the screen

where the spectator sees Tagore's signature on the page of Sandesh.

Tagore's soulful lecture read in Shantiniketan after Sukumar's untimely

demise and Tagore's visit to him on his

deathbed were also mentioned in the

commentary rendered.

Surprisingly, Satyajit Ray omitted

two vital facts that relate to Tagore and

his father.

One is an iconic photograph of

Tagore taken by Sukumar Ray; it was

not mentioned in the film, and another

fact that went unmentioned is Tagore's

special preface written for Sukumar's

first story book, Pagla Dashu, published in 1940, 17 years after his

demise.

Ray tried to include every single

creative merit that Sukumar Ray

showed in his short life as an editor,

illustrator, club secretary, organiser,

photographer and even as an activist

in Brahmo Samaj.

His proficiency in technology,

whether it is modern printing or photography, was vividly mentioned in the

film; however, Ray missed to mention

that Sukumar was a very good organ

player and music composer, as well as

a merit Satyajit

himself

inherited from a man with whom he

did not interact much in real life.

Another vital side of Sukumar Ray,

which his son did not mention in the

documentary, was that he was a science fiction writer and a contributor

of serious articles to leading publications both in English and Bengali.

While in London, Sukumar, an

avid follower of modern printing technology and photography, wrote two

serious articles in Penrose's Pictorial

Annual. He also contributed an article

to Probashi. Recently, an article published in Ananda Bazar Patrika by

Goutam Chakraborty on 24 September

2023, has shown the vast arena of natural science, astronomy, industrialisation, history and civilization to which

Sukumar contributed 105 articles in

his edited magazine Sandesh, along

with at least 16 biographies of titans

like Charles Darwin, Joan of Arc, Livingstone, Florence of Night, etc.

In the 1920s, Sukumar inserted

the idea of sending man to the moon

through a firework rocket in a writeup and also clarified the evolution theory of Charles Darwin for his young

readers. Considering all these extraordinary articles written by a young editor of a magazine, Debasis Mukhopadhay, in an article published in Aajkal

dated 30 October 2022, it is very rightly

said that it was Sukumar Ray who

upgraded the child magazine Sandesh

magazine from a child magazine to a

new age teen magazine when no one

in India ever thought of such an idea.

It is unfortunate that this amazing

side of Sukumar Ray was not boldly

mentioned in the script of Satyajit

Ray's documentary. He had the chance

to throw light on this side of Sukumar

Ray rather than give too much importance to the enactment of his plays.

While trying his best to project

Sukumar Ray as a mature, talented literary figure not confined to

the small world of children's

literature, Satyajit Ray simply

overlooked a wider spectrum of his

father's work.

The documentary is a good example of self-control exercises.

Satyajit had every easy scope to

overload the script with many short

interviews and bytes of elderly people,

including himself, talking about Sukumar Ray, but he did not include any.

His own name comes only once when

commentary runs to describe that in

1921, Sukumar's wife Suprabha gave

birth to a son, and the newborn was

named Satyajit.

It was the point where emotional

turmoil could have overtaken Satyajit

Ray. He could have added information,

like that his name was initially decided

to be Prasad, which was later changed

to Satyajit. He even did not mention the

only recollected memory of him with

his father seeing a steamer going on the

Ganga in Sodepur. All these small titbits, which have huge personal value

but are not that important for common

people, were smartly and ruthlessly

avoided. In this regard, Ray has shown

his global standard as a filmmaker.

To make the audience understand

Sukumar Ray's ability as a playwright,

Ray screened three of his plays in small

fragments. Noted actors like Utpal

Dutta, Soumitra Chatterjee, Chiranjit

Chakraborty, Santosh Dutta, Tapen

Chatterjee and young students of

Patha Bhavan School were cast. While

The character of Santosh Dutta in the

play "Ha Ja Ba Ra La" was shown in

shadows and made a profound impact

in the film. The play "Lakshmaner

Shaktishel" is covered for a longer

span, and Tapen as Hanuman and

Soumitra as Ram enacted the play like

any normal play. A song by Anup

Ghoshal was also included in it.

The best thing about this documentary is that Ray did not try to show

Sukumar Ray as a writer only meant

for children's literature. The entire

effort given by Ray in this film is to

show Sukumar as an exceptionally talented man who is equally comfortable

in the worlds of science, the arts, and

commerce as well.

The documentary ends with the

last stage of Sukumar's life and finally

his premature death when he was at

the apex of his creativity. In his many

poems, Sukumar was slowly expressing his impending death in a pensive

tune, and Ray made Soumitra read one

of his last poems, which talks about

ending his song "Ganer Pala Sango

Mor .

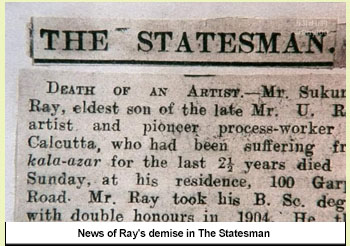

Ray showed clips of many newspapers reporting the untimely death of

Sukumar Ray, and in that, The Statesman was shown with the wrong masthead. As an avid reader of The Statesman from his early teens, this should

not have been overlooked by Ray.

Satyajit Ray scholar Debasis

Mukhopadhay thinks that it will be

unfair to compare Ray's other classical documentaries with this Sukumar

Ray, which he did inside the studio

and even some work at his home.

Debasis, who is one of the best

collectors of anything related to Satyajit Ray, thinks the flashing of various

characters in Sukumar Ray's writing

shown in the beginning of the film

itself is a little amateurish, and Ray's

inability to take a camera outdoors is a

big drawback of the film. Debasis

reminded me that this is the only documentary Satyajit Ray made in which

he himself did not do voiceover commentary in his signature baritone, and

this is his only documentary made in

Bengali. The rest of the four are all in

English, and he himself is the voice

behind the screen.

No master has all his work equally

great. So is Satyajit Ray. Considering

his physical limitations at the time of

making this documentary, the tight

budget provided by the Government

of West Bengal, and the additional

mental pressure of not falling into any

trap of being overly emotional, Satyajit

Ray tried his best in his last documentary that he made after many years.

The Sukumar Ray documentary,

directed by Satyajit Ray, was to be

released on 30 October 1987, on his

100th birthday at Nandan. As the hall

was not available, it was released a day

later, on 31 October 1987, in the presence of Jyoti Basu and the director

himself.

Click here to view the original article

|