| FRAGMENT OF MEMORY LEFT BY THE BRITISHERS |

|

In today’s Shillong, the glory of the past is painfully shadowed. Much has been destroyed due to unplanned urbanisation. Yet a walk in this hill town reveals its pristine colonial past, writes Somen Sengupta

The history of the British East India Company’s arrival in India and its gradual encroachment into our political arena are mostly discussed in the context of three major regional zones. How a group of traders from a foreign shore first became political agents, then power brokers, and finally political challengers to vanquish all mighty rulers of Bengal, Bombay, and Madras Presidencies to take over a country many times bigger than their own is perhaps the biggest watershed mankind has witnessed. In this journey of history, one often overlooks the East India Company’s invasion of Assam and lower Himalayan region.

The history of the British East India Company’s arrival in India and its gradual encroachment into our political arena are mostly discussed in the context of three major regional zones. How a group of traders from a foreign shore first became political agents, then power brokers, and finally political challengers to vanquish all mighty rulers of Bengal, Bombay, and Madras Presidencies to take over a country many times bigger than their own is perhaps the biggest watershed mankind has witnessed. In this journey of history, one often overlooks the East India Company’s invasion of Assam and lower Himalayan region.

Ever since Bengal was conquered and Calcutta became one of the biggest centres of the Empire, officers of the British East India Company were desperate to explore and capture the Himalayan foothills of Assam where three small hill ranges — Khasi, Jayantia, and Naga — prevailed with scanty tribal population. After the first Anglo-Burmese War, the East India Company realised the importance of logistics connection through Assam. It was in 1829 when David Scott, a British agent who later became the first Governor of Assam, negotiated with local rulers to form a British base at a place called Nongkhlaw. From there, they moved to Cherrapunjee in 1835. The Britishers found both places dull, and in 1864 after coercive negotiation with a local Khasi leader, they got a place of their choice. The place they selected had an excellent climate almost like that of England and Scotland. Moved by its serenity and charming weather, they developed another hill station near Shillong peak of Khasi hill and named the town after that peak.

It was the beginning of the story of Shillong, the quaint hill town which was the Capital of the British administration of Assam and East Bengal for many years. Till 1972, it was the Capital of Assam and then became the Capital of newly formed State, Meghalaya. Shillong was perhaps an enigma to our European rulers. The growth and development of Shillong was always low profile when compared to Darjeeling or Shimla, the two major British hill stations which were always buzzing with social and political affairs.

It was the beginning of the story of Shillong, the quaint hill town which was the Capital of the British administration of Assam and East Bengal for many years. Till 1972, it was the Capital of Assam and then became the Capital of newly formed State, Meghalaya. Shillong was perhaps an enigma to our European rulers. The growth and development of Shillong was always low profile when compared to Darjeeling or Shimla, the two major British hill stations which were always buzzing with social and political affairs.

Unbelievable as it may sound, Australian firs and rare eucalyptus along with English fruits and flowers were planted across the town by Britishers to give it a look similar to their home. An old letter found in archives states that many Britishers found the weather here in the first six months similar to that of west England, while the remaining six months were said to be even better than England.

Thus the attraction of Shillong to Britishers posted in Assam and nearby. Away from all attention, here at Shillong, a mini Scotland was forming since 1870s. There was obviously no snowfall but there were mist and fog between pine woods and cold mountain air that wooed a large number of European tea planters, traders, Armymen, and other officials ever since it was made habitable.

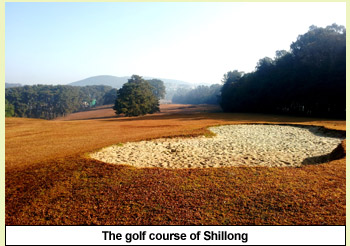

Gradually everything that is British started coming up in Shillong. From a golf course to polo ground, from an elite social club to churches — all that was typical of a European settlement came up on the landscape of Shillong. With that a large number of cottages and palaces started dotting the hills, giving it an almost complete incarnation of a European town. Such was the love for Shillong that many Englishmen named their homes after places in England, like Starmore or Bonny Brae or Crow Borough.

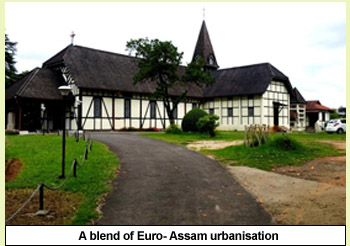

In today’s Shillong, the glory of the past is painfully shadowed. Much has been destroyed due to unplanned urbanisation. Yet a walk in this hill town reveals its pristine past and clearly shows how the construction concept changed over the century. The early colonial buildings were mostly made of bricks and tiles, while after the 1897 earthquake, log houses with tin roofs became the order of the day. It was more of a blend of European cottages with Assam’s roofed hut houses.

In today’s Shillong, the glory of the past is painfully shadowed. Much has been destroyed due to unplanned urbanisation. Yet a walk in this hill town reveals its pristine past and clearly shows how the construction concept changed over the century. The early colonial buildings were mostly made of bricks and tiles, while after the 1897 earthquake, log houses with tin roofs became the order of the day. It was more of a blend of European cottages with Assam’s roofed hut houses.

This Euro-Assam blending is palpable in the most famous church of Shillong — the All Saints’ Cathedral. First built in 1877, the church was reduced to rubble in the 1897 earthquake that changed the city forever. It was rebuilt in 1902 with a unique design befitting a hill station. Reverent Herbert Pakenham Walsh was one of its first chief priest. The educated and well-cultured man was fond of Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore and expressed his wish to meet him when the poet was travelling in Shillong. Unable to keep his request, Tagore in return sent him a new English poem in 1922. This is perhaps the only poem Tagore wrote exclusively for a religious head.

The brown and golden wooded church is simple yet beautiful. Its central prayer hall has exclusive wooden craft and the walls are full of dedicatory tablets to departed soldiers and other great souls. Many tablets are dedicated to those who died in the First World War. One tablet is about a doctor named Violet Annie Jackson, who died on December 5, 1920, and is described as “a resident of Assam for many years”.

The oldest church of Shillong is Anglician church built in 1874. Near the All Saints’ Cathedral stands one of the biggest relics of the Raj. It is the Shillong golf course built in 1889 with nine holes and then expanded to 18 holes in 1924. It was here that the royal citizens of Shillong relaxed after a long day in office or on a Sunday morning. Many social relations of that community were made and broken here over a glass of whisky or a round of golf. Even today, the golf pavilion reminds one of a bygone era. Its decor, vintage photographs, cane furniture, and architecture are a perfect flashback of that era. The club house facing the golf course offers a breathtaking view of the vast green surface surrounded by the deep pine forest.

This golf course is actually an appendix of the elite Shillong Club. Established in 1878, this is one of the oldest British clubs involved in various sports like golf, football, polo, and horse racing. Once an exclusive place for Europeans and Indian royals, the club has witnessed the most elite sections of this hill town. Now open to many members from the local community, it also runs as a hotel. Its interiors haven’t changed much; the old fireplace is still logged and the wall full of trophy heads of wild animals shines every evening when members gather here.

This golf course is actually an appendix of the elite Shillong Club. Established in 1878, this is one of the oldest British clubs involved in various sports like golf, football, polo, and horse racing. Once an exclusive place for Europeans and Indian royals, the club has witnessed the most elite sections of this hill town. Now open to many members from the local community, it also runs as a hotel. Its interiors haven’t changed much; the old fireplace is still logged and the wall full of trophy heads of wild animals shines every evening when members gather here.

Once the European community of Shillong was so orthodox that one was not allowed to settle down in some places if he/she wasn’t “Western” enough. However, from 1920s, things started changing. Rich and famous Indians started rubbing shoulders with white lords and as a culmination, the zamindar of Mayurbhanj of Orissa and the royal families of Tripura, Manipur, and Nepal purchased houses here.

Bir Bikram Manikya, a member of Tripura’s royal family, was so enchanted with the place that he built a 10-room summer retreat here named Tripura Castle. Now converted into a high-end heritage hotel and renamed Royal Heritage, the palace is another piece of European influence. It was here that Tagore spent some days and the hotel still has a table used by him.

Another heritage building, Pine Wood, is now a hotel run by the Meghalaya tourism department. Earle Holiday Home, a typical English country house of 1920s, is now used as a mediocre hotel.

The Don Bosco Centre of Excellence has several exhibition halls preserving an excellent saga of Khasi hills history and its regal past under the British rule. It is not only golf and cottages that were beloved to the Britishers in Shillong. A plethora of lakes and waterfalls, which decorate the panorama, were also a reason why they made this place their home for many years.

The Don Bosco Centre of Excellence has several exhibition halls preserving an excellent saga of Khasi hills history and its regal past under the British rule. It is not only golf and cottages that were beloved to the Britishers in Shillong. A plethora of lakes and waterfalls, which decorate the panorama, were also a reason why they made this place their home for many years.

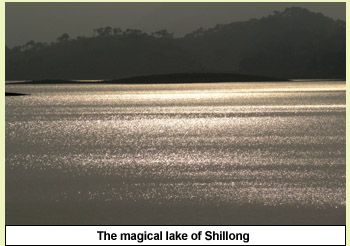

One such waterfall is Sweet falls where the stream falls from 200 ft onto a rocky stone bed. It is the wild surrounding where colonial citizens came for hunting and picnics. Ward lake, which was planned by the Britishers, is still the heart of the city, while Umian lake — a huge water body created from the water flow of Umian river in the process of generating hydro power — is now known as the most beautiful lake of Shillong. Umian in Khasi language means water of the eyes. It comes a few kilometres before Shillong. Though it has no direct link with the Raj and the people who used to stay in Shillong, it gives a clear idea how Shillong looked like till 1950s before becoming an overgrown urban jungle.

Today’s Shillong cares less about its British past. It is no more a hill town where the best of colonial diplomats and elite lived. The race course is long shut and the club is now almost a public place. Shillong is now a hub of English and Khasi rock music of the North-East and the nerve centre of Indian football. With the setting up of the Indian Institute of Management, Shillong is now becoming cosmopolitan and its new citizens no more love to play polo or golf. They are the smartphone generation engrossed in a virtual world.

The British legacy of Shillong thus awaits a silent and not very peaceful death.

The only legacy that keeps the torch burning is Shillong’s extraordinary craze for football. One cannot just discard England totally when it co-existed with them for two centuries.

This article was published in The Pioneer on 1st October 2017

Click here to view the original article

|